As published by VICE on June 2, 2014

Twenty-seven-year-old Qusai Zakarya woke up at about 4:30 AM on August 21, 2013. He rolled out his prayer rug inside his family’s two-bedroom apartment in the small town of Moadamiya, Syria, and started his morning prayers.

Alarms coming from nearby Damascus interrupted his daily ritual. After two years of revolution, Qusai had gotten used to the near constant shelling and bombings, but something was different this summer morning. The alarms were the kind “you usually hear in movies about World War II when there is a big air raid,” he told me.

“Within seconds, I started hearing rockets flying into the ground,” Qusai recounted. They hit the rebel-held town about 500 feet away from him.

“Before I realized what was going on, I lost my ability to breathe. I felt like my chest was set on fire. My eyes were burning like hell, and I wasn’t even able to scream to alert my friends,” he said. “So I started beating my chest over and over until I managed to get my first breath.”

As Qusai recovered inside his home, he heard people screaming on the streets. A neighbor pounded on his door and asked for help. Her two kids were suffocating and vomiting “weird white stuff,” Qusai said.

They rushed onto the street to seek help and found a “terrifying” scene. Men, women, children, elderly people were “running and falling on the ground, suffocating, without seeing a single drop of blood or knowing what was really going on,” Qusai told me.

Qusai spotted a 13-year-old boy left all alone, suffocating and vomiting. Qusai ran to him and gave him CPR. “He had big wide blue eyes and was almost staring into another dimension. He was suffocating, and he seemed to me very innocent to die this way or any other way,” Qusai said.

A friend in the Free Syrian Army (FSA) brought his car to transport wounded to the local field hospital—a poorly equipped center with eight doctors for the town’s nearly 14,000 people. They packed the car with six children and three women. Qusai and the wide-eyed 13-year-old boy sat in the trunk together on the way to the hospital.

Hundreds of people, all exposed to sarin gas, had already arrived seeking help. More than 550 people in Moadamiya were exposed that day, according to Qusai.

Placed Among the Dead

As Qusai started to get out of the vehicle, he felt himself fading away. He fell to the ground and lost consciousness. Then his heart stopped.

Qusai later learned that his friends took his body inside the hospital. Doctors gave him CPR but couldn’t bring him back to life. They put his body in a pile of other Syrians killed by the attack.

That could have been the end for Qusai. Fortunately, 45 minutes later, a friend saw his body. Crying, the friend came over and started shaking his limp corpse. Qusai made slight movements. So doctors worked to revive Qusai, giving him extra shots of atropine. They washed his body with cold water repeatedly, trying to cleanse him of the chemicals. Half an hour later, Qusai woke up.

“I was standing in the street near the field hospital wearing nothing but my underwear. I was almost freezing because my body was covered with water. I was trying to understand what was going on, because everything was going in slow motion for me,” Qusai said.

Syrian President Bashir al Assad’s military forces were taking advantage of the panic. They attacked the town on the ground with special forces, all wearing full chemical protective gear. Artillery units fired on the town. In the air, regime jets dropped bombs onto the town. “The earth was literally shaking under my feet when I woke up,” Qusai said. “They used an unbelievable amount of power.”

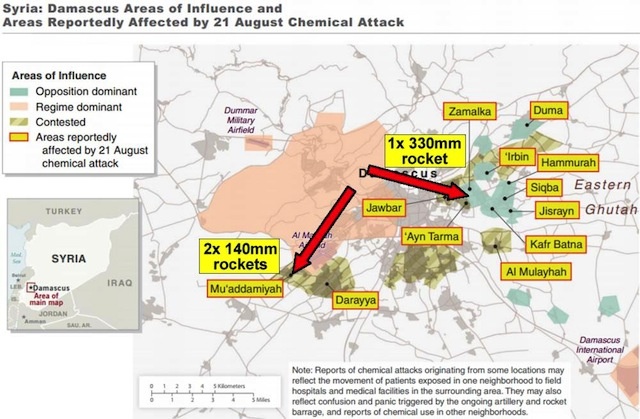

The chemical weapons attack was part of a concerted effort to take the town back from the FSA. Located less than 10 miles from downtown Damascus, rebel-held Moadamiya is a key strategic gateway on the southwest of the capital. It’s also positioned near important military assets—the barracks for the Presidential Guard, the al Mazzeh Military Airport, the Air Force Intelligence Directorate headquarters, and the main base for the Fourth Armored Division, headed by Assad’s brother Maher.

Despite their best efforts, the regime failed to take back the town from rebel control that day.

Eighty-five people in Moadamiya died after being exposed to the sarin gas. Another 50 people were killed by the subsequent artillery shelling, bombardment, and ground offensive, according to Qusai.

“There are no words to describe the horror of that day,” Qusai said.

The World Turns Its Attention to Syria

The regime’s sarin-gas-filled bombs harmed thousands and killed an estimated 1,400 Syrians throughout Damascus that day.

Graphic images of piles of Syria children killed by the chemical weapons quickly dominated the news. This wasn’t the first chemical weapons attack, but the visuals and massive numbers set off international demands for retribution.

In Washington, President Barack Obama threatened Syria with a military strike. A few months prior, the White House had concluded that the Assad regime had used chemical weapons to kill 100 to 150 Syrians in multiple previous attacks.

“The president has been clear that the use of chemical weapons—or the transfer of chemical weapons to terrorist groups—is a red line for the United States, as there has long been an established norm within the international community against the use of chemical weapons,” the White House announced on June 13, 2013.

Syrians celebrated, thinking that even with the horrors of the chemical attacks, the West would finally take down Assad.

I was in Turkey when the chemical weapons fell on Moadamiya. Via Skype, I talked to Syrians in Damascus who had survived the chemical weapons attack. The following day, I walked the short distance across the border into Syria and met refugees fleeing the country. They feared future chemical weapons attacks and demanded American action.

Meanwhile, United Nations weapons inspectors came to Moadamiya to examine the patients and gather evidence. Qusai escorted them to the hospital, translating and explaining what had happened. Assad’s soldiers shot at the UN vehicles and bombed the town, yet they still examined the survivors, took blood and tissue samples, and looked at the remnants of the rockets.

The evidence was clear. But polls showed that 75 percent of Americans opposed a military attack against Syria. Obama changed course. “I’m ready to act in the face of this outrage,” he announced on August 31, 2013, just ten days after the attack. Obama acted by deferring to Congress to make the decision.

With the British parliament rejecting a motion to join the United States in a military strike against Syria, Congress looked ready to vote against American action. They weren’t interested in getting involved in another faraway conflict—even though more than 100,000 Syrians had been killed at that point. (Since then, the death toll has risen to 150,000.)

Obama asked Congress to delay a vote. Instead, Syria’s ally Russia brokered a deal for international monitors to destroy Syria’s chemical weapons and production sites.

I could feel the anger and disappointment building in Syrians. They had believed in Obama and felt betrayed. The “red line” had been crossed back in June. Just another broken American promise.

“It was absolutely disgusting for me,” Qusai said. “I was feeling angry and disappointed because we were reaching out to the entire world, asking for help, and no one stepped in. Nobody did anything, after the chemical attack.”

Kneel or Starve

The regime had another tactic in its arsenal: starvation.

Because of the rebel resistance, the regime shut off Moadamiya from the world, besieging it since early November 2012. The military forces shut off all the basic supplies of life: power, water, gas, and food. “Everything was forbidden,” Qusai said, in an effort to displace people and disrupt the rebellion.

No one is permitted to leave or enter the city, not even humanitarian aid workers. People attempting to leave get shot at by regime snipers. Qusai said he helped bury “a lot” of civilians who tried to flee.

Abdul Hamah, 42, tried to sneak out of Moadamiya in January 2013 to get medicine for his seven-year-old daughter. The regime caught him, tortured him to death, and dumped his body on a nearby road, according to Qusai. The soldiers attached a note to his body that stated: “This is what’s going to happen to anybody who’s going to try to come in or out from Moadamiya. It’s either Assad, or we’re going to burn the country.”

Previous food stockpiles of rice, sugar, and noodles started to run out after about seven months, just before the chemical weapons attacks. “We had nothing to survive on,” he said. During the siege, Qusai lost 30 pounds. (He has since recovered mostly, weighing in at about 165 pounds now.)

People in Moadamiya turned to their olive trees, which are hundreds of years old. They subsisted on olives and tree leaves to make “something like a salad or a soup – anything that can keep us going,” according to Qusai. It was clearly not enough.

“People were literally becoming like ghosts,” Qusai said. “Their faces are pale, their voices have become weaker. You can look at people’s eyes and see how tired they are and how desperate they are as well.”

The town’s doctors gave vitamins to malnourished patients, but their supply was limited and insufficient to treat the widespread problem. Within a few months, a total of 12 people died from starvation—seven children, three women, and two elderly people.

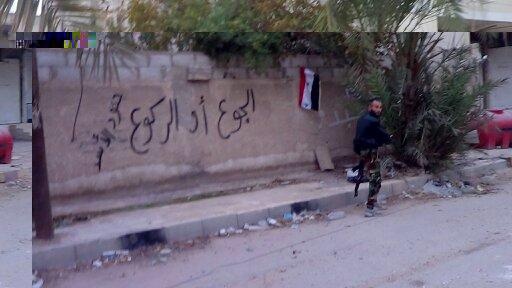

Regime forces had written “Kneel or Starve” on building walls in Moadamiya. “It’s an organized policy. It’s a weapon of war, starving people to death,” Qusai said.

Life under Siege

All public services in Moadamiya were halted, including schools, but doctors ran a field hospital out of a 900-square-feet basement with ten beds for 30,000 people.The town’s three previous hospitals were destroyed by regime military attacks. (Mosques and schools were also destroyed.) After the siege began, only five doctors and three medical school students remained.

More than 400 people in Moadamiya died due to lack of medical care, according to Qusai. “The doctors were almost helpless,” Qusai said, while crediting them for doing the best they could, like “performing heart operations with a flashlight or sometimes a candle.”

Regime jets bombed the town on a nearly daily basis. Helicopters indiscriminately dropped barrel bombs (filled with explosives, nails, and other materials), falling wherever the wind took them. Syrian military troops on the ground fired artillery shells at Moadamiya every day. When I talked to Qusai and other activists in the town over Skype, I could hear shelling in the background.

Qusai claims more than 600 people were killed and 900 injured in these attacks. Most of the victims were women and children.

Locals, including Qusai, formed a relief committee to supply people with food and help with other needs. The committee gathered food stocks and kept it in a storage area, distributing it to those who need it most (mostly families with women and children).

At the same time, Qusai and others besieged the UN, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and other international organizations for humanitarian aid. “But nobody was able to do anything or nobody did anything, because I know if there’s a will there’s a way, but nobody had a will to help us,” Qusai told me.

The UN tried to bring in food, but the Assad forces stopped them from entering the town.

Life under the siege was “unbearable,” Qusai said. He tried to explain it to me: “Imagine yourself waking up one day and knowing that you don’t have any food in your house, and when you want to go and get some food, you’ll just see soldiers shooting at you, you’ll see bombs and aircrafts falling on your neighborhood and on your street.

“When you come back home, you’ll see your family, your children, your sister, and your wife starving. They’re literally starving to death; they’re hungry, and you cannot do anything to help them. Imagine how frustrating and heartbreaking that is,” he said. “I really hope that nobody [has to] live in a similar situation.”

Qusai points out that millions of Syrians across the country are also without education, medical care, and safety.

Civilians Permitted to Leave Moadamiya

With his excellent English skills and internet access, Qusai became a spokesman for the town, speaking regularly to international media hoping for an intervention. I first spoke with Qusai in October 2013 and wrote one of the first pieces about the blockade on Moadamiya for VICE. Three days later, the State Department took notice and called on the regime to allow for humanitarian access.

The regime finally agreed to allow civilians to leave the town. About 4,500 people—mostly women, children, and the elderly—were taken outside Moadamiya by bus to the nearby al Mazzeh Military Airport.

As they arrived, however, most of them were arrested or executed, according to Qusai. Women were raped. Families were robbed. “Even some small kids died under torture,” he said. Hundreds are still missing.

![On a wall in Moadamiya: “Where is the [regime] security service to challange us? This is Moadamiya, and God is with us.”](http://baddorf.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Syria-Is-Obamas-Rwanda-6.jpg)

Trading People for Food

The remaining thousands of people in Moadamiya still had no food or access to humanitarian aid. The regime offered to provide food only if the rebels surrendered. That wasn’t an option for the people of Moadamiya.

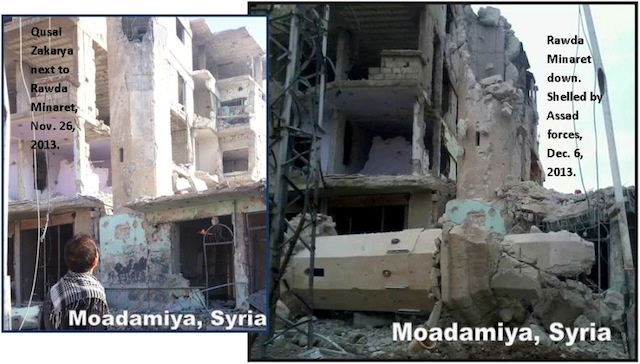

Though he was already starving, Qusai started a hunger strike on November 26, 2013. The peace activist blogged about the nonviolent action daily and called on people outside Syria to join him.

Activists, human-rights defenders, congressmen, academics, and thousands of Americans supported his effort by joining together in an International Solidarity Hunger Strike started December 20, 2013. More than 30 towns in Syria faced similar blockades, affecting more than a million people. They continued until January 22, 2014, when the peace talks between the Syrian government and the rebels began in Geneva.

Qusai didn’t eat for 33 days, stopping his hunger strike on December 28, 2013, due to “health issues.”

Two days prior, the Moadamiya local council, run by the opposition, had signed a truce with the Syrian government.

Looing back, Qusai told me he wasn’t happy with the results of his hunger strike because the international pressure didn’t force the regime to end the siege.

Instead, the town accepted piecemeal deals from the regime in exchange for food.

When the locals raised the Syrian government flag on the highest landmark in town, the military sent the first shipment of food in 15 months. “It was less than a meal per person—400 grams [less than a pound], maximum. Rice and sugar. One and a half pieces of bread,” Qusai told reporter Michael Weiss.

Then the rebels traded a captured armored truck. More food came.

The Fourth Division soldiers then asked to interrogate specific rebel soldiers in Moadamiya. They said they “just wanted to have a talk with these people,” according to Qusai. About 100 young men in low-level roles surrendered themselves. Some volunteered to turn themselves over. More food arrived.

Heavy and light weapons were also swapped out for more food shipments. “We gave them 20 AK-47s, most of them not even functioning well. Another shipment came,” Qusai explained.

Now, the town council raises money from its residents to pay the regime exorbitant amounts for minimal food to keep everyone alive. The siege continues.

A Great Escape

After the truce was signed, more than 7,000 people returned to the town, including government spies. “I stopped feeling secure after the truce. The town was open and I felt they could get me any second,” he explained.

His fear was justified. The regime had noticed Qusai. “If you want the truce to go smoothly, shut up Qusai—for good,” said Ghassan Bilal, the chief of staff of the Fourth Armored Division in January 2014. Bilal supposedly to co-opt Qusai.

Two weeks later, the mukhabarat got in touch with Qusai. Guaranteeing his safety, they offered to escort him to the nearby 4th Armored Division headquarters in Damascus to meet with Bilal.

The regime had “demanded that certain activists in Moadamiya leave as a condition of the truce,” according to a February 3, 2014, post on his Facebook page. Qusai initially opposed the truce and still advocated for a complete end to the siege. In part, he eventually agreed to meet with Bilal “due to increasing pressure from residents who want the food shipments.”

Under pressure from the locals, Qusai agreed to talk. Soldiers took him to the Dama Rose Hotel in Damascus, where he stayed for four days. It was his first time leaving Moadamiya since the siege began 15 months prior.

Over the course of several days, Bilal tried to convince Qusai to work with the regime by telling international media that conditions had improved in Moadamiya and throughout Syria. Qusai told the military commander he needed time to think about it.

While Bilal leveled with Qusai, the secret police came to Qusai’s hotel to arrest him. While they were kicking and punching him, Bilal’s soldiers appeared just in time to stop them.. Qusai thinks it was an elaborate ruse—an attempt to make Qusai trust Bilal.

Really, Qusai had no choice. Refusing would likely have meant being indefinitely imprisoned, tortured, or killed. So Qusai lied and told Bilal he would tell international media that all was well in Syria.

Qusai convinced Bilal that reporters wouldn’t believe him while on regime territory, and that he needed to go to Lebanon.

Bilal “was stupid enough to believe me,” Qusaid said. He was escorted to the border and used a fake passport with a photo that didn’t even look like him to get into Lebanon.

Sure, he was free but still feared attacks from Syrian agents. Qusai spent every moment with foreign reporters. “Even in Lebanon, I knew that there was somebody watching some way or somehow,” he told me.

Both the Syrian regime and the Russian government tapped his cell phone. “Sometimes I heard people opening the lines and talking in Russian, and other times I heard the answering machine of Syriatel network,” he said.

Working with American activists, Qusai secured a tourist visa to the United States

To get out of Lebanon, he first had to get past agents of the Iranian-controlled Hezbollah in the Beirut airport. “I really felt like Ben Affleck in [the movie] Argo,” he said. Only once the plane was airborne did Qusai feel truly safe.

He arrived in Washington, DC, in March on a tourist visa.

The Consequences of Obama’s Betrayal

Ultimately, Qusai blames President Barack Obama.

Since he arrived in the United States, Qusai has been on a speaking tour across the country, mostly at universities. He meets with American policymakers in DC, including senators and representatives. He talks to journalists and uses social media to explain the situation in Syria. He’s writing his autobiography. “I am doing my very best to raise awareness,” he said. His goal is to get people to support the Syrian revolution.

I met Qusai in New Haven, Connecticut. He’d come to speak to a group of law students at Yale University. We’d talked by phone for hours already, but I wanted to meet him in person. As I listened to him tell his story in a classroom, I realized his description of what happened to him was nearly identical to what he told me. He used the same powerful phrases and expressions to explain it. It was like a politician’s stump speech.

“How do you feel telling the same story again and again?” I asked him after his presentation.

“I feel noxious sometimes,” he told me, “because I’m telling the story over and over, almost every day with media or during the events, and it’s just so disgusting and pathetic that all of that happened and it wasn’t enough to have the international community and the United States, President Obama doing anything against the Assad regime—to show any kind of consequences for the chemical massacre, at least.”

Among others, Qusai has met with the US assistant secretary of state for democracy, human rights, and labr; the US National Security Council’s senior director for the Middle East and North Africa; and other directors at the National Security Council at the White House. Additionally, Qusai conducted a briefing for 20 officers and officials from the US Department of State and the US Department of Defense. Qusai has also met with senior aides on the Republican and Democratic staffs of the House Foreign Affairs Committee.

Everywhere he goes, American officials say they want to do more for Syria but say they’re stopped by the White House.

“A lot of high government officials are pissed” about Obama’s inaction, Qusai said.

UN Ambassador Samantha Power Wants to Do More

In an hour-long, one-on-one talk at the United Nations, US ambassador to the UN Samantha Power compared the situation in Syria to what she witnessed in Bosnia as a war correspondent. In her book, A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide, Power argues that the US could have saved tens of thousands of lives in Bosnia and Rwanda. During her conversation with Qusai, Power hinted at how more lives could be saved if the United States did more in Syria too.

“In her writing and thinking, Ms. Power often divides US officials into those who pressed for action [on past wars] and those who found reasons not to get involved. As a member of the president’s cabinet and America’s representative to the United Nations, she may well have to decide into which category she falls,” journalist Raf Sanchez wrote in theTelegraph last year.

Power can’t speak out directly or publicly against America’s foreign policy, but some Syrian activists told me she should take a moral stand by resigning in protest of American inaction and work outside of the government to save Syrian lives. Career diplomat Fred Hof, for example, resigned from his role as the lead diplomat tasked with leading negotiations to end the Syrian conflict and has since been a strong advocate ofengagement in Syria.

A few weeks after they spoke privately, Power invited Qusai to attend a May 22 meeting of the UN Security Council. The council voted on a resolution to refer the situation in Syria to the International Criminal Court. After China and Russia predictably vetoed the resolution, Power asked Qusai to stand in the audience as she told his story. “The Syrian people will not see justice today. They will see crime, not punishment,” she said.

“Ambassador Power was the first person who had the courage to open and read one of those messages from the Syrian people,” Qusai wrote on his blog.

Qusai said Obama has made “a big mistake” in not responding and should “stop trying to reason with a lunatic”—Bashar al Assad. “This is a very bad message that he’s giving right now to all the lunatics for power, like North Korea, or Iran,” he said, comparing Obama to a child closing his eyes and hoping bad things will go away.

This inaction has “terrified a lot of people even inside of US government,” Qusai said. He didn’t want to name “high-profile people” who criticized Obama’s foreign policy, because they spoke to him in confidence.

Qusai advocates for a no-fly zone to stop the Assad regime from bombing civilians. This would negate the need for providing anti-aircraft missiles that could fall into Islamist hands. Qusai also wants more anti-tank weapons for the rebel, saying that could change the course of the war. Many of the American officials he met want these things, too.

“Unfortunately, dictators only understand the language of power,” Qusai told me.

Qusai believes it could also make the regime take negotiations seriously and start handing over power. During the Geneva talks, the regime tripled the number of barrel bomb attacks on Aleppo. People on the ground referred to them as “Geneva Barrels.” The continued killing of civilians “showed the world once again that the regime is not interested in having any political settlement in Syria,” Qusai said.

With limited weapons and funds coming in from the United States, Syrians are turning to unwelcome terrorist groups like the al Qaeda–linked Islamic State of Iraq and Syria. These Islamists “are getting stronger on a daily basis,” according to Qusai, by gaining sanctuaries and invaluable battlefield experience in their attacks against moderate rebel groups and regime forces. “You can’t buy experience,” Qusai said.

Getting Iran or Russia to stop supplying weapons to Assad’s military could also change the balance of power, he said.

Qusai predicts a bleak future for Syria if Assad remains in power. “We will see only more suffering and more misery coming to the Syrian people,” he said. But with new political leadership, Qusai said, “it will be the first and true chance of peace in the Middle East.”

Support for Syria

Kenan Rahmani, the director of operations at Syrian American Council, has been traveling with Qusai across the US since March and sees Qusai as an inspiration for activists like him. “He seems to be very, very hopeful,” the law student told me.

“He is always believing strongly that Syria is going to be free, going to be the Syria we dream of, even if it takes 20 years, but eventually we’ll all go back to Syria and live in a democratic Syria that we dream of,” said Rahmani, a Syrian-American whose grandfather was jailed and tortured in Syria by Hafez al Assad.

Qusai is always coming up with new ideas to get people thinking about Syria, according to Rahmani. For example, Qusai is working on a letter writing campaign directed at the White House to ask for President Obama to “stop the genocide in Syria and help the Syrian people to win their freedom.”

Qusai will be speaking on June 5 at a United Nations panel on the Syrian regime’s use of starvation as a weapon. Today, across the street from the UN headquarters in New York, he and other supporters will read out the names of 100,000 Syrians killed since the revolution began. People in Syria, Turkey, and Paris will also read the same names.

Qusai is also participating in the Blood Elections campaign. Activists reject the presidential elections scheduled for Tuesday while the regime continues its “shelling and killing [of] civilians.”

When people ask Qusai what they can do to help, he tells them to raise awareness of what’s actually happening in Syria, especially through social media. He tells people to talk to their Congressional representatives. He also asks that they donate to nonprofit organizations supporting people in Syria.

Moadamiya Siege Continues

The checkpoints, the troops, the snipers, the tanks, still surround Moadamiya. Now some people in Moadamiya are providing aid to civilians in Darayya, a neighboring town also under siege. The bombs continue to fall from the sky, tumbling from the backs of helicopters, in an effort to deter support for other Syrians in need.

More than 150,000 people have died since the conflict began in March 2011. “It’s just like you’re sitting there and waiting the next day and who’s going to die next,” Qusai told me. “I lost most of my childhood friends, friends from high school, from junior school.”

Nearly 3 million Syrians have fled the country. Another 6.5 million are displaced within Syria. Thousands have been tortured. The regime has used chemical and conventional weapons against civilian populations. While chemical weapons are being dismantled, regime aircraft are dropping chlorine-filled barrel bombs on rebel-held areas.

To get some perspective on these numbers, I stopped by Arlington National Cemetery on a recent trip to DC. More than 300,000 Americans are buried in those fields. I walked through the gravestones for about 15 minutes and found a spot in the shade to work on this piece. It’s hard to imagine all the careless loss of life that’s taken place on the other side of the world and the loss that continues today.

Looking at the “normal lives” of people here in the United States, Qusai said, “it just doesn’t seem right to me to see all of going on in the world and people are just moving on with their lives, like nothing is going on somewhere else.”

People in the United States are “blessed” to have power, food, and safety, Qusai said. “They take it for granted. They don’t hug their family and friends tight like we do, because they don’t feel that this might be the last time they might see them,” he continued. “They don’t understand. They just don’t.”

“But this is going to change. I will speak, scream, and write, until they start listening, until they understand,” Qusai said.